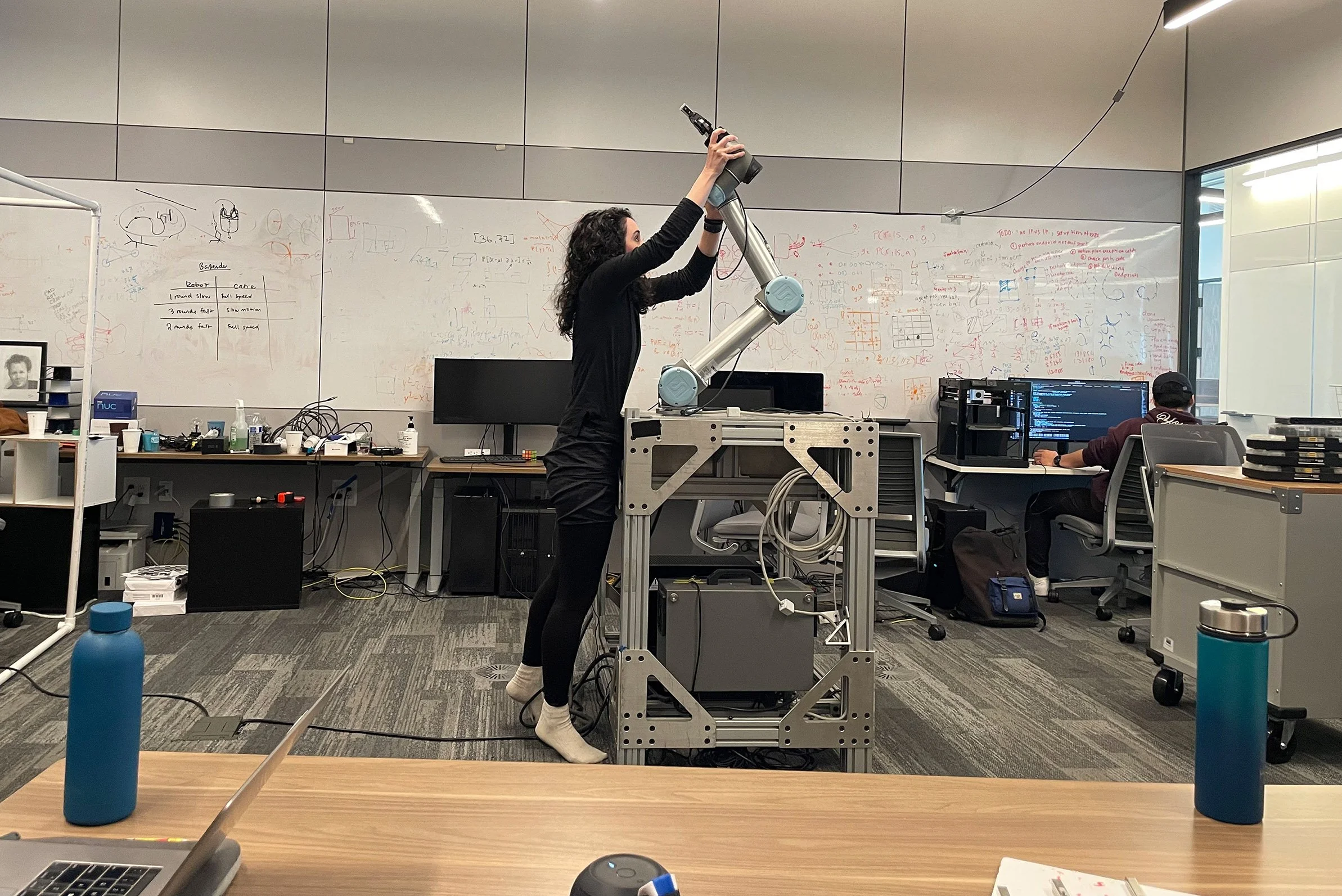

Catie Cuan dancing with the UR5e robot arm in "Breathless" on December 16, 2023 at National Sawdust in Brooklyn, New York. Photo credit: Catie Cuan & Ken Goldberg

Are robots coming for us and our work?

The dystopian answer to that question is clearly “yes,” a perspective that has dominated our conversation about artificial beings ever since the word “robot” was introduced by Czech playwright Karel Čapek in his 1921 dark comedy, “R.U.R.” or “Rossum’s Universal Robots.” But the fear of machines replacing humans goes back even earlier, to the Industrial Revolution and the birth of the modern factory. It’s an anxiety we’ve been living with for a few hundred years.

What’s new are the first glimpses of robots moving from an industrial setting into our homes, offices and public spaces.

Will we embrace their presence, like we did when computers took their place alongside the pencils and paper on our desks?

Will the robots move in a way that’s comfortable and familiar, or will we recoil from the strangeness of the interaction?

What kinds of work will we allow them to do for us? Household tasks? Food service? Caregiving?

Will we accept robots as partners, or do we keep our distance?

There is no easy answer to any of these questions. But now is the time to ask them.

That’s what dancer/choreographer/engineer Catie Cuan and artist/researcher Ken Goldberg did in an eight-hour time and motion performance called “Breathless: Catie and the Robot” that premiered on December 16 at National Sawdust in Brooklyn, New York.

“Breathless,” which was commissioned by Jacob’s Pillow and NationalSawdust+, and sponsored by UC Berkeley’s AUTOLab, pairs Cuan with a UR5e robot arm made by Universal Robots. What unfolds over the duration of a workday in “Breathless” is an eloquent dialogue in movement between human and machine.

“Humans have a marvelous range and plasticity,” said Cuan in an interview. “My grandmother had a sixth-grade education. She was born in Cuba, lived there her whole life, and worked in a cigar factory rolling Partagas cigars. Her body was able to do that labor and it became a way for her to support her family. We wanted to show the poetry of that motion as opposed to what the prevailing media narrative is, that it’s denigrating humans and saying they’re immediately replaceable.”

With a Ph.D. in robotics and AI from Stanford University, and a background in professional dance, Cuan is an advocate for a more nuanced approach to integrating robots in the workplace. Robots are predictable, untiring, and can be quite precise, but according to Cuan, they lack empathy and the ability to do more than just one thing.

Ken Goldberg, Professor of Industrial Engineering and Operations Research at University of California Berkeley. Photo credit: Ken Goldberg

It’s not a small distinction. Her collaborator, Ken Goldberg, Professor of Industrial Engineering and Operations Research at University of California Berkeley, is in awe of human dexterity and flexibility, especially when it comes to grasping objects, the long-term focus of his research.

“I was recently in Mexico City and there was a guy playing a leaf,” recounted Goldberg in an interview. “He was able to get sounds out of it that were astounding, just by squeezing and twisting it in subtle ways. We have nothing like that in robotics—the hand’s ability to sense and touch and adapt to an object. There’s nothing even close.”

From rehearsal to performance

Cuan and Goldberg began exploring the concept behind “Breathless” in 2021. In mid-2023 they brought on composer Peter van Straten and producer David Imani. Two undergraduates from Goldberg’s lab at Berkeley, Ethan Qiu and Shreya Ganti, rounded out the team as robot motion engineers.

“Because the robot was so heavy we did most of our work and rehearsals in the lab,” said Qiu in an interview. “Not to mention we also had music blasting on large speakers,” continued Ganti. “Catie needed the full space to dance so the other student projects were cramped into a corner. We really have to thank them for bearing with us while we got through the process.”

Catie Cuan rehearsing with the UR5e robot arm in Berkeley's AUTOLab. Photo credit: Ken Goldberg

By late autumn of 2023 Ganti had mapped all the desired motions onto the robot joints and Qiu had fail-safed the software pipeline. What remained was a critical series of performance-length dress rehearsals.

Goldberg admits that the intensity of those sessions took him and his engineering students by surprise. “We have to treat this rehearsal as a real show and you need to know what it feels like when things break,” Cuan remembers telling her colleagues. “Because if you don’t rehearse that and then you have a big show with 200 people watching and you’re in New York City, you can’t whisper to me on stage when something goes wrong.”

“Engineers tend to be fairly dismissive of artists,” said Goldberg. “Working on this project, I was reminded that making artwork is as challenging as research.”

An environment of creativity and invention

Though not a performer, Goldberg is an accomplished artist in his own right. He has been creating and exhibiting multimedia and telerobotic art since the early 1990s, and he brings that artistic mindset to his research and teaching at Berkeley.

A former student, Stephen McKinley, was one of those who found a home in that unique interdisciplinary atmosphere. After bouncing between different labs and not getting along with advisors, McKinley wandered into Goldberg’s lab and showed him his sketches, drawings and paintings. Before long they were deep into a discussion about the creative process and the transition from art to design to engineering. “It was the start of an extremely productive relationship. Ken has been a powerful mentor to me for many years now,” said McKinley in an interview.

As a youngster, McKinley spent summers in his aunt and uncle’s metalsmithing studio. “They’d be making a complex piece and would put me and my brothers to work cutting things out with a saw or planishing a bowl with a hammer or sanding something,” explained McKinley. “That experience taught me to respect the process of working with one’s hands and getting to know materials. It gave me a huge leg up in engineering school because I understood how metals moved and how they fatigued and broke.”

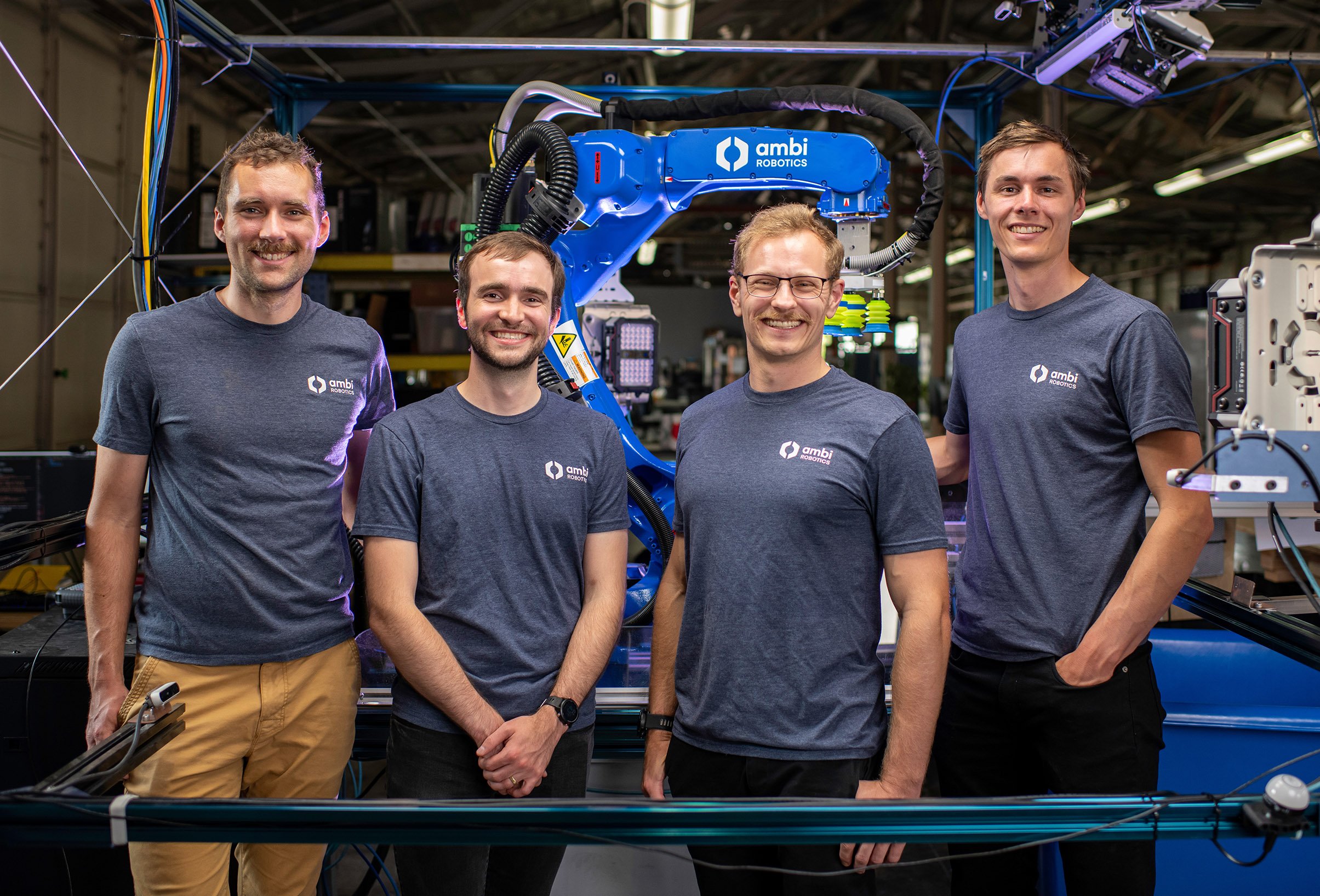

Co-founders of Ambi Robotics, from left to right: Stephen McKinley, Matt Matl, Jeff Mahler, and David Gealy. Photo credit: © 2021 NIALL DAVID

After getting his doctorate in mechanical engineering at Berkeley, McKinley co-founded Ambi Robotics with three classmates from the AUTOLab and his mentor, Ken Goldberg. Now VP of Operations at the growing package sorting company, McKinley still looks to the human hand as a model for the motion and cognition behind their products.

“It’s a beautiful problem trying to recreate human dexterity—something that can manipulate unknown objects,” said McKinley. “At the end of the day though, you need to function within constraints, because even people have constraints. And if you want to make something that’s universally useful, it’s not going to be applicable everywhere. So what we’re doing at Ambi is creating machines that can handle any unknown object you might throw at it within the constraints of it being a package.”

Pushing the limits of a machine for art

Some of the most astonishing and dramatic moments in “Breathless” come when Cuan slides up to the robot arm, her head just inches from one of its large metal joints. She reaches in, almost caressing the arm, and gently pushes and pulls it through a sequence of movements. Then she lets go, and the robot replays those exact motions as she dances alongside—a 21st century pas de deux.

Just a few years ago this artistic intimacy between human and machine would have been impossible. Robots that move with the agility and speed of the UR5e were always sequestered behind heavy cages. But a new generation of collaborative robots, “cobots,” rely on exquisitely sensitive sensors and software to gain an awareness of the people around them.

“This is very exciting because you can stand next to a cobot and if it did swing and hit you on the arm it would stop immediately,” explained Goldberg. “It might give you a bruise but it wouldn’t break your arm.”

That kind of force sensing is, obviously, designed as a safety device. But the team behind “Breathless” turned it into a creative tool. “Even though [the UR5e] is a cobot and it’s meant to be contacted, I think we took that to an extreme,” said Cuan. “I was contacting it low to the ground, high up, and at various parts all along the robot.”

Following on the success of that experience, Goldberg plans to explore the limits of force sensing with other projects in his lab. “We learned that we could control it within the robot, something we never understood how to do before,” he said. “So we’ll be actively using force sensing in our research going forward, rather than seeing it only as a braking system.”

Humanity’s future is with robots

The Nobel Prize-winning scientist Richard Feynman believed that the best way to understand something thoroughly was to teach it. Even better if you could teach it to a child. Had Feynman lived a few decades longer he might have added, “or to a machine.”

This is the gift of living in an age of AI and robotics. For the first time in history we are teaching the essence of what it means to be human to machines—our creativity to AI, and our dexterity to robots. In return, we are learning so much about ourselves.

Maybe that’s too optimistic and we should be preparing ourselves for a bleaker future, where machines and people compete for resources, attention, even survival.

But if the creators of “Breathless” have a say, it’ll be different—a future of collaboration, a partnership between human and robot. Something more like a dance.

The choice between those two visions will be made by the next generation. It’s up to the rest of us to make sure that wonder and passion is what drives them, not fear.

“When Catie was in the lab, dancing and working with the team, all the students were inspired,” said Goldberg. “Everyone got to experience what that was like, not only Shreya and Ethan. They were curious about it and it opened up their horizons. The student who’s comfortable with that, that’s the kind of student I always want.”

—

Published here on Forbes.com

March 24, 2024