The next generation of virtual worlds must focus on our shared humanity. That’s why EY’s Cognitive Human Enterprise and the New Museum’s NEW INC are bringing together artists and engineers to imagine a different kind of metaverse. Photo credit: EY

The metaverse is having its Wild West moment. Facebook has renamed itself Meta and is promising to create a virtual world for the masses. Microsoft is building Microsoft Mesh, its own version of that world for enterprise. The chipmaker Nvidia has its Omniverse, a platform for collaborative 3D design. And the virtual landscapes of Roblox and Epic Games are already the online home for hundreds of millions of gamers worldwide.

But it’s not just technology companies who want to define this alternate reality. For professional services firm EY (Ernst & Young Global Limited), knowing that their clients rely on them to understand what is changing about how people live and work means jumping into the metaverse themselves.

Since June of 2021, a team at EY called the Cognitive Human Enterprise has been building a virtual world with a motivation very different than the tech giants. Their aim is to apply the full diversity of human imagination to make that virtual world, called the EYVerse, as generous and welcoming as possible.

Must your avatar look like you?

One of the challenges facing every metaverse builder today, according to Domhnaill Hernon, engineer and Global Lead of the Cognitive Human Enterprise, is that we don’t yet have the technology to create fully naturalistic human avatars. Despite advances in skin and movement rendering, most avatars that strive for ultra-realism fall short of what feels natural. Instead, they find themselves in the dreaded “uncanny valley,” where real human beings are often unsettled by an almost-person who seems... not quite right.

The team at EY’s Cognitive Human Enterprise takes a different approach. They have launched an artist-in-residence program in partnership with the NEW INC incubator at the New Museum and made it a key part of their metaverse design practice.

“A lot of people develop technology without thinking about the human at all,” explained Hernon. “They think about the user and the consumer, but not about what it means to be human, how we see ourselves and how we see others. When we work with artists what we get is deep thinking about technology through the lens of the human condition. At EY, our language is ‘humans at the center.’ And artists, in my view, are the ones who take that to an extreme.”

Hernon’s strategy is to bring together artists and engineers—professionals with different backgrounds, different training, and different ways of thinking about problems—to explore some of the most confounding issues surrounding the metaverse and virtual worlds.

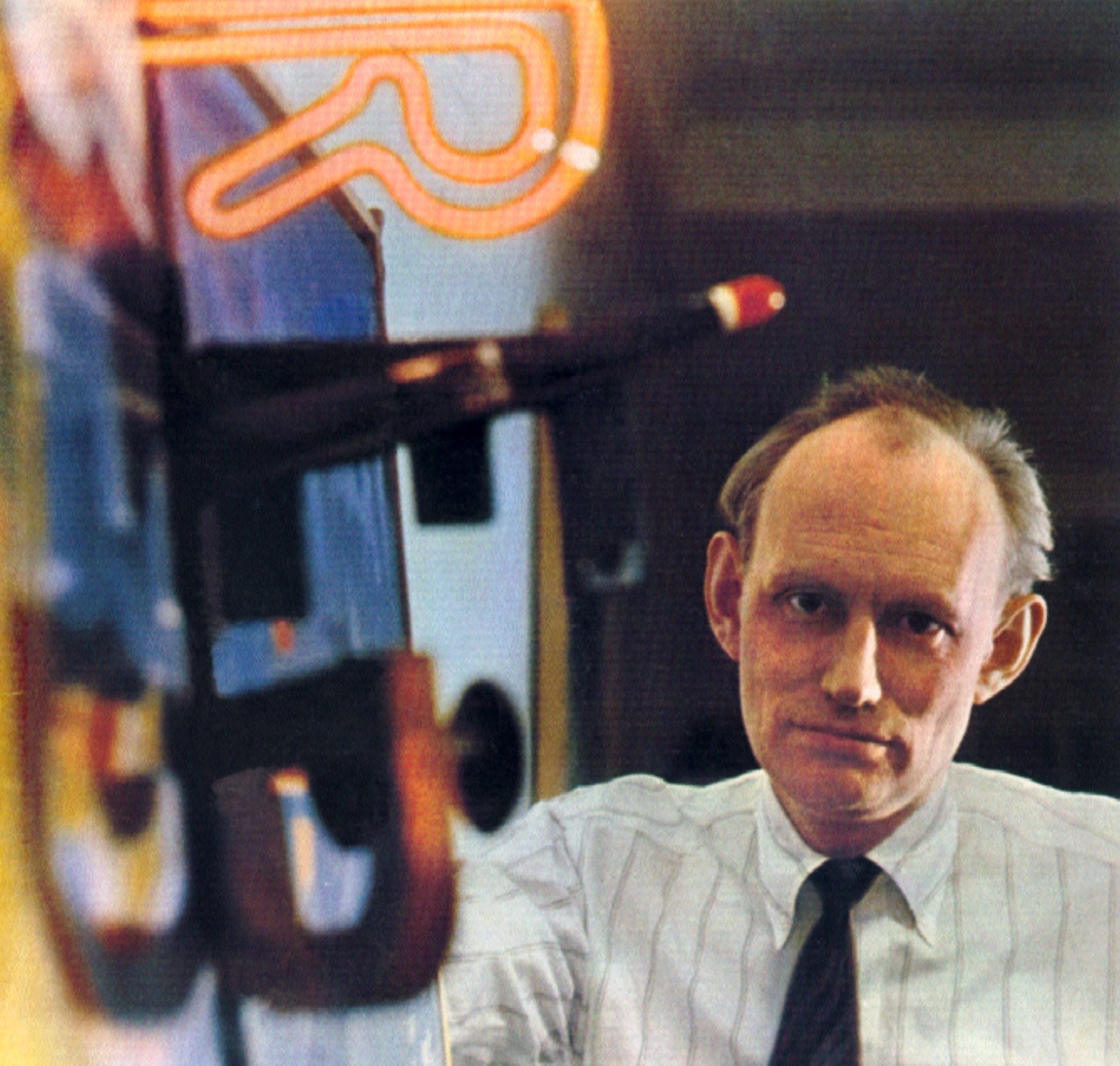

Billy Klüver, co-founder of E.A.T., next to the Field Painting by Jasper Johns of 1963-64. Engineers from Bell Labs helped Johns create the battery powered neon "R" in this work. Photo credit: Experiments in Art and Technology

It’s not an entirely new approach. Before EY, Hernon was at Nokia Bell Labs, where he was responsible for resurrecting its storied Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) program. Started in 1966 by Bell Labs engineer Billy Klüver and the artist Robert Rauchenberg, E.A.T. brought together engineers and artists to create new works of art and explore the boundaries of tech and arts collaboration.

Though successful in its time—E.A.T. helped to inspire the modern multimedia arts movement—the formal program was abandoned in the 1980s. But in 2016, at celebrations of E.A.T.’s 50th anniversary, Hernon decided that those interdisciplinary collaborations were too valuable to stay dormant. He restarted E.A.T. at Bell Labs, called the Nokia Bell Labs E.A.T. initiative, but with a different focus—to humanize technology.

For five years Hernon steered the re-energized E.A.T. program in this new direction, inviting multimedia artists like Sougwen Chung and Lisa Park, composer Seth Cluett, and beatboxer Reeps One to partner with researchers at Nokia Bell Labs, all exploring new ways for human beings to communicate and connect.

Then, in June of last year, Edwina Fitzmaurice, EY Global Chief Customer Success Officer, recognized the value of these artist/engineer collaborations for a company getting into virtual worlds and recruited Hernon to EY. “What Domhnaill brings to the party is that we are trying to solve a human problem rather than a technology problem,” said Fitzmaurice.

An ancient tradition inspires a new idea

Josie Williams is a multimedia artist studying in the Studio Art MFA program at New York’s Stony Brook University and research assistant to artist and professor Stephanie Dinkins. As one of the resident artists with the Cognitive Human Enterprise she has been exploring alternatives to realistic human avatars for EY’s metaverse.

“My primary ethnicity is West African,” said Williams. “And it’s traditional in West African cultures at group gatherings or celebrations, that there are always people who wear masks to represent the ancestors. It’s like the ancestors are here with us. The mask itself isn’t the ancestor, but it’s a reminder that their words are still around.”

Mask and models, studies for EY artist-in-residence Josie Williams's project, Ancestral Archives. Photo credit: EY

Inspired by a contemporary and ancient tradition, those West African masks show up as chatbot avatars in Williams’s residency project, Ancestral Archives. And that, in turn, has sparked new ideas for the Cognitive Human Enterprise team.

“We don’t need to build avatars that are humanoid in their expression. Talking with Josie about masks was something that unlocked this idea,” said Hernon. “The way she represents AI bots through masks opened our minds to issues of accessibility, representation and identity. How do you build solutions that operate on a spectrum—where you meet people where they are in the moment, in the virtual environment of their choosing? That’s why working with artists like Josie is so important for us.”

EY’s commitment to artists and the process of invention

Even though Williams and the Cognitive Human Enterprise team have been working together for more than half a year it’s just the start of their collaboration. This is by design.

“The way we work with artists is in two parts,” explained Hernon. “First is the residency phase. They come in and we talk about big topics, big themes—lots of open knowledge and collaborative sharing. But eventually there’s always one thing we’re coming back to in our conversations. Then we sit down together and say, ‘This is what we’re excited about. We see this as different and valuable. Let’s have a thesis and let’s experiment against that thesis to round out our thinking and check that we have something real.’”

“We ask the artist, ‘Can you propose to us a commissioned piece of work where we take this as experimentation and a proof of concept?’ And we actually build it out to solidify our thinking and share this new knowledge with the public. That’s phase two.”

It’s also a recognition that creativity takes time and attention. Both the artists and the team at EY’s Cognitive Human Enterprise make a commitment to work through their points of difference, find common ground, add context along the way, and then build something worthwhile. Hernon has developed this approach through years of guiding artist residencies, and he knows that to get value out of a collaboration, it can’t be rushed.

For Williams, letting her imagination run free within the structured process of the EY residency has given her a new confidence in her work. “I knew what I wanted, but they’re helping me figure out how to make it happen. The ideas we’re discussing aren’t linear but the production of it is very much like boom, boom, boom. They have the creative energy and spirit of, ‘Oh yeah, that’s going to get done.’”

Bringing touch and feeling to the metaverse

Kate Machtiger is an artist and designer, and, currently, Creative Director at Set Creative. She’s also autistic and credits her neurodivergence for giving her a unique approach to the challenge of shaping virtual worlds.

“Part of the collaboration [with EY] is about the ways my neurodivergent perspective influences their thinking and how that adds diversity of thought to the design,” said Machtiger. “Having a hyper-awareness of my environment allows me to pick up on things that other people might not, and also notice when they’re missing in a virtual space.”

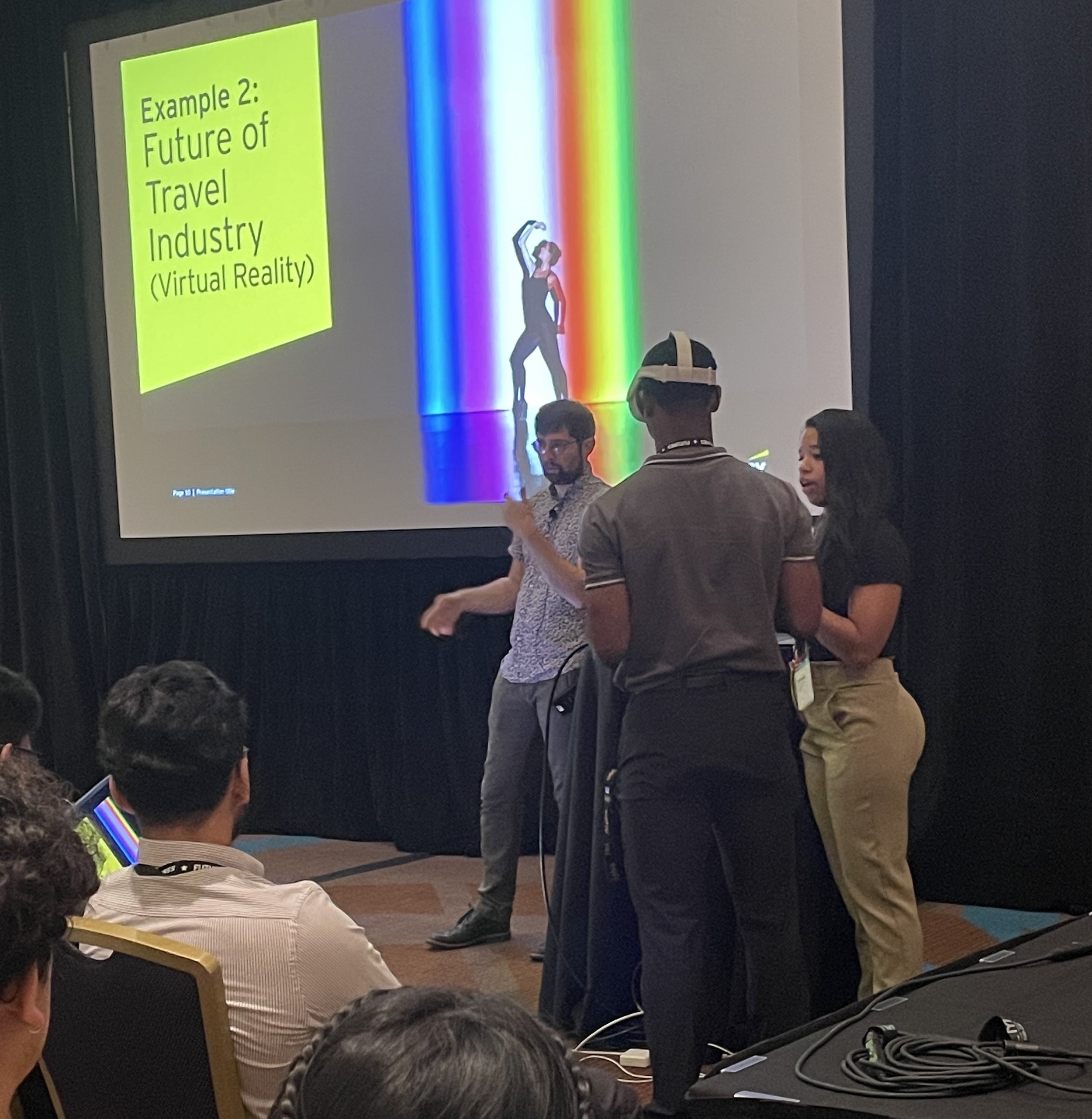

Working as an artist-in-resident on the Cognitive Human Enterprise team, Machtiger has helped EY creative technologists Danielle McPhatter and Ethan Edwards explore solutions to the lack of a varied sensory experience in the metaverse.

EY Creative Technologists Ethan Edwards and Danielle McPhatter demonstrate virtual reality and metaverse technologies at EY Futures 2022. Photo credit: EY

“When we go from the physical world to the virtual, we lose out on so many senses,” explained McPhatter. “The visual is there—and we’re visual dominant—but we’re missing spatial audio, and how it affects our perception of ourselves. And touch is completely absent in those environments. Kate thinks about how to bring in elements of those experiences in ways we couldn’t even imagine.”

Picture an object covered in a fuzzy or furry material. We all know what it’s like to run our fingers through textures like that. Those tactile experiences, according to Machtiger, imprint themselves into our embodied memory. Then, later, with just a visual prompt of a texture, our brains can faithfully recreate that sensation. Using cues like that enhances our participation in the metaverse without relying on expensive, and still very limited, haptic technology.

“We’ll have an hour-long conversation with Kate and there’s two or three things she says that can open up a whole new perspective on our work,” said Edwards. “Abstract concepts that neither of us have fully articulated end up becoming concrete—the cornerstone for some of these virtual worlds. I think of Kate saying, ‘Not only do we need to work around this limitation, but we can use it in interesting ways that are not part of the standard pipeline, the standard rule book.’”

What’s the value of having an artist on your team?

Anyone who manages an artist-in-residence program in a corporate environment has to advocate for its worth. Skepticism from leaders and colleagues can be hostile, but more often it simply comes from not understanding the value of the program.

“When people hear art, they think we’re going to fund you and your team so that you can put up a painting in a gallery,” said Hernon, addressing a common misconception. “No, you’re going to fund our team so we will take all the insights and knowledge and lived experience of people who see the world totally differently. And then we’re going to build that into solutions that you’ll take to the world and add value.”

For Hernon’s colleague, Edwina Fitzmaurice, there’s another—maybe even more fundamental—reason for a company like EY to pursue these collaborations. “I often say when you speak the truth, it has a ring to it. Like the ting of a glass. People will listen carefully and engage. We’ve had that kind of reaction to this work, which is, it’s coming from a place that is authentic. You don’t have to agree with it, but it’s real and reality has a ring to it. People hear it. Sometimes that’s enough.”

Looking down the road

What’s in the future for the Cognitive Human Enterprise? As the program matures, Domhnaill Hernon wants more employees to have the opportunity to connect with artists and learn from them. Using the model developed in New York and London, Hernon is looking at similar artist/engineer collaborations for EY’s technology and innovation hubs in continental Europe and Asia.

And with that international growth he wants to broaden his team’s focus to explore how technology can enhance human capabilities and help people become more creative, not just make a faster process or cheaper product.

From left to right: Edwina Fitzmaurice, EY artist-in-residence Reeps One, and Domhnaill Hernon presenting at SXSW 2022. Photo credit: EY

If tapping into the wisdom and imagination of artists to find value for business seems far-fetched it’s worth remembering that other once fringe ideas are now common, with their own metrics and a tangible return on investment.

“This is a movement,” observed Edwina Fitzmaurice. “It reminds me of the way CSR used to be off to the side of an organization—corporate social responsibility was considered to be for a specialist group only. Then it came to the center. Sustainability is the same, as is diversity, equity and inclusion. Those too came to the center. We’re now at a similar moment with the arts where we can bring that to the center. It’s also good for artists, who deserve to be recognized for the value they bring to the world. So when we put the arts in a business context, everyone wins. And we want to lead the way.”

--

Published here on Forbes.com

August 4, 2022